The Economic Theory Of Selling WordPress Themes

As you’ll know if you’ve read my recent post, I find practical applications of economic theory quite an interesting topic.

With the topic of WordPress theme pricing coming up again this week on WPCandy, with WPZOOM co-founder Dumitru Brinzan’s announcing the launch of his $200/theme niche theme shop, Hermes Themes, and what with my ongoing experiment in WordPress theme pricing with my free/pay-what-you-want theme, Empty Spaces, I thought it’d be interesting to get the Economics textbooks back out and look at the actual theory behind how WordPress themes are priced.

This post aims to look at two things: why WordPress themes are priced how they are, and what changes could be made to that pricing in order to generate higher profits for those making the themes.

There’s a little bit of economics you’ll need to understand, but I’m fairly confident I’ve explained this clearly. If you’re ready, then, let’s get to it!

Stagnating pricing

As far as I can tell the price of a WordPress theme hasn’t really changed much in the five or six years premium theme shops have been around.

This is odd for two reasons: first, you’d expect with the vast increase in the quantity of WordPress themes being sold, there should be a correlating decrease in price due to increased competition.

Second, WordPress themes have become immensely more complicated in the last five years, and the time you had to put in to turn a top quality theme in 2008 nowhere near reflects the time one needs to put in now to turn out a product of the same quality.

So what would one expect to have happened? The price of a WordPress theme should have been fluctuating, reflecting the market conditions of quantity of competing products and the cost of producing the WordPress theme.

In practical terms, it would seem prices should’ve fallen between 2008 and 2010, with those prices climbing back up 2010-2011 and 2012 to the present seeing a plateau. This reflects very general market conditions of rapid expansion in supply early on, followed by heavy development time as theme businesses fought to become sustainable, and most recently the establishment – and rewards gained from – economies of scale.

Let’s stick that on a graph. This is simple economics: increased competition and supply drives prices down; prices are then rising as product differentiation and economies of scale establish strongholds in the market. Continued competition ensures prices do not rise too far.

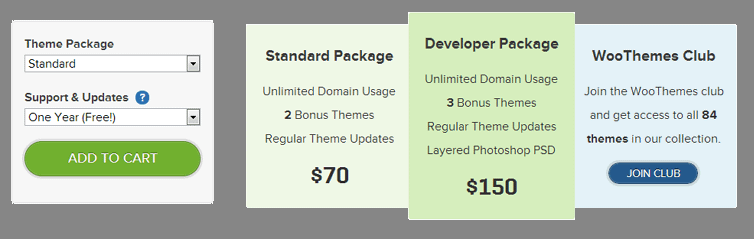

But… I don’t really think this has happened, though. Whilst you can get a theme on ThemeForest for $30, WooThemes will still happily sell you a theme for $70. Let’s take a look at why this hasn’t happened.

Not all themes are equal

My lovely graph, based on lovely sound economic theory isn’t correct as it makes the fundamentally flawed assumption that all WordPress themes are equal products.

You knew that, right? It’s obvious — I’m not even talking in “quality” terms; if I want an “acadmenic” theme, then the latest magazine theme from ThemeForest isn’t a product I’m going to consider. If I want a portfolio theme then I’m not going to look at Woo’s latest e-Commerce design.

Thus, prices haven’t fallen because whilst overall the supply of WordPress themes has increased, the supply of directly-comparable WordPress themes has not increased on anywhere near the same scale.

This explains why the average price of a “magazine theme” is likely around $40, whereas as “premium framework” will set you back $60+. There are vastly more magazine themes to choose from, which has driven prices down.

The economics is working, just on a much smaller scale.

Revenue maximisation

Now we know why prices are at the levels they are, let’s look at the theory behind the question everybody selling themes wants to know the answer to: will I make more money selling more themes at a lower price, or selling fewer themes at a higher price?

I should note, I don’t have the actual answer, but I can explain to you the theory which will allow you, dear theme shop owner, to find the answer yourself.

If you plot a graph of price against revenue, you generally find the results are normally distributed — ie you get a bell curve — and if you start with the highest possible price, you’ll see as price decreases revenue increases from higher sales, up to a point at which despite higher sales, the low price means revenue decreases.

It’s everyone product seller’s dream to be at the very top of this curve, a point which is known as the revenue maximsing point. Such named because it’s the point at which you have highest revenue. Economists are imaginative, eh?

One should note for WordPress themes, the profit maximsing point may be slightly either side of the revenue max point as support costs don’t directly scale, but it shouldn’t be very far either side of this point, to the point we’ll assume it’s virtually the same.

If you put all of that into another nice graph, it looks like this:

Looking at the prices, it’s fairly easy to see the revenue maximising point is around $50 -$70 for your average WordPress theme. That’s around the standard price of a WordPress theme, so it would seem everyone’s got their pricing right and the free-market has done its job.

Costs that don’t scale

However, the theme market may have just one last twist in store for us: the assumption that the revenue maximising point is close to the profit maximising point could well be entirely flawed.

There’s various bits of anecdotal evidence around to suggest support costs are actually huge. WooThemes’ recent switch to one-year-only support for new customers was a move cited as a result of spiralling support costs. Hermes Themes’ announcement that themes were going to be priced at $200 cited the cost of support. From my own experiences as a theme-shop “support expert”, I can certainly believe support costs can eat up around 1/3 to 1/2 of revenue.

If that’s the case, then profit may be higher from the selling of fewer themes to fewer people at a higher price.

Let’s look at that same graph again, just with profit maximisation marked on too:

As a good capitalist, you should be interested in the blue line, which shows profit. What does the graph show? Profit is highest when selling themes at around $95 and — more significantly — the modal (most common) price of $50 actually makes vastly less profit.

The graph is saying that you’d definitely make much more money (that you can keep!) from selling fewer themes at a higher price. Selling a higher quantity of themes at a lower price looks like it’s actually a really bad idea.

I should note these figures are entirely made up and I have designed them to give the results I want. However, I believe these are roughly the figures you’d get if this was tried as a proper experiment.

Innovation… in pricing

I hope, then, that this has been food for thought. I was prompted to write this by looking at the stats from my new free/pay-what-you-want theme, Empty Spaces. The more people that look at it, the better the data I’ll have when I write up the results in a couple of weeks 🙂

The economics in this post is a bit rough around the edges and is there to prove a point rather than illustrate outstanding economic theory. If I’ve got something wrong or something needs better explanation, let me know — leave a comment below!

[…] The Economic Theory Of Selling WordPress Themes – This post aims to look at two things: why WordPress themes are priced how they are, and what changes could be made to that pricing in order to generate higher profits for those making the themes. […]

I was wondering where you got the data for these enlightening charts until I read that. Thanks for pointing that out. 😉

I think the most interesting point you make is that less sales for a higher price can mean the same revenue but with less support burden and therefore more profit. That sweet spot must vary depending on the type of theme (some themes must require more support), level of support offered (unlimited sites, one site, one year, lifetime, forums, tickets?), and so on. For one shop it might be $90, for another maybe $50.

I imagine the only way to find the sweet spot is to get your feet wet.

The data is an educated guess, and I reckon it’s not too far off from what you’d find if you actually did this — and, of course, it will vary depending on individual costs. I’d be very interested to see if anyone tries this!

Interesting post. I’ve sometimes been a bit bothered by the open source mandate that you should give away the product and make your money from support, which doesn’t scale.

Support costs become a bigger issue when a business is selling a subscription. Some, like WooThemes charge a startup fee plus $25/mo. I guess they’re betting that regular users that are paying monthly become experienced enough to require little support. If not, that $25 could get eaten up pretty quickly.

Maybe the most profit would come from selling themes cheaply, at the greatest possible volume, but with no personal support included?

I think WooThemes in particular have found support costs to be a big problem — hence the changes they made last year, with the switch to only one year of support from the time of purchase.

The most profit’s going to come from selling themes at the profit maximising point, though. As one of the graphs above showed, it’s likely that point comes from selling fewer themes at a higher price.

Another thought .. You could wisely divide the work a business has to do by theTYPE of labor.

Right now, I am a solopreneur WordPress developer, whose main selling point is that I can figure out stuff other people can’t, and can explain things to non-techies in ways others can’t.

But this is a self-limiting niche. If every job I do is custom, it’s hard to replicate *patterns* that reduce the work intensity in relation to results achieved. If I can find ways to create results through patterns—without reducing the patterns to things that are *easy* for everyone to do—then I would have a good market.

So, if I sell a product, then I might have to be the senior architect, that gets paid the most to manage that project; the other programmers could get paid less, perhaps. And then the support staff could be trained to recognize and respond to the same patterns again and again in supporting that product. Therefore—in the nature of work—they could be paid a lot less, in fact.

In other words, I would think that the labor costs for support could be significantly lower than those for development.

An interesting point – I think that’s where a lot of theme shops start out, but certainly from my experience there’s only so far that that scales. If the entire product was built around patterns, though? Could be on to something there…

Excellent, Alex!

I just appreciate, that you are starting to think like a businessman about it all .. as it seems that that is probably rare. A very maturing business, eh?

People most often don’t like to look at numbers.

Great insight about theme pricing with the help of graph. I took few economics classes so I can easily understand what you mean 😉

As a theme developer, I’m more to separate the cost between price of theme and price of support. Users pay for the theme and get free support for few months or year, and after that when they need support they have to pay.